structural challenges to technological emancipation:

socially necessary discipline

The interplay between discipline and freedom, how the former generates the latter and the latter requires the former has been a critical dilemma since the beginning of civilization. Without going into the rich philosophical literature on the question of freedom, I would like to outline two paradigmatic examples which epitomise the contradiction, one institutional, and one industrial.

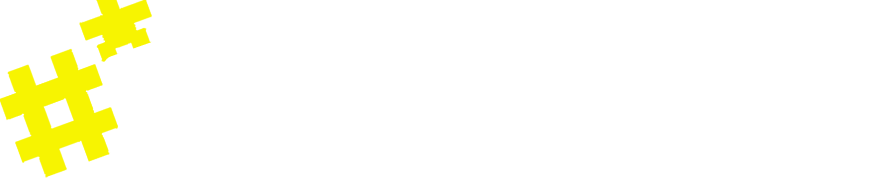

No civl society exists without what I call “the hard shell”, the complex of border fortifications and installations and the personnel which monitor, maintain and provide its more reactive and spontaneous functionality. The officers of the State administration on duty at the frontiers are not free, they must adhere strictly to their instructions, and should an “order” be dispensed from somehwere higher in the very rigid hierarchy within which their duty has bearing, they must unquestioningly obey the order and enact its contents.

The discipline structures of absolute control in the military sector of the society function to provide the spaces where civil peace may prevail, the peace which is required for differing opinions to result not in desperate violence but rather in leisurely conversation and accommodating encounters. Today’s prevalent notion of the virtues of the secular civil sphere: freedom of opinion, freedom of expression, etc. are completely beholden to the freedom from immanent mortal threat provided firstly by the “hard shell” at the borders and secondarily by the “radical lattice”: the structure of administrative laws, manifested physically where necessary in the bodies of policemen, and increasingly in mercenary-type security employees who uphold either state-sanctioned or privately decreed regulations on acceptable behaviour. This radical lattice with its regular machinic availability is also the material infrastructure of the civil sphere, the power grid and Internet, the sewage system and the labour provisioning system which maintains these.

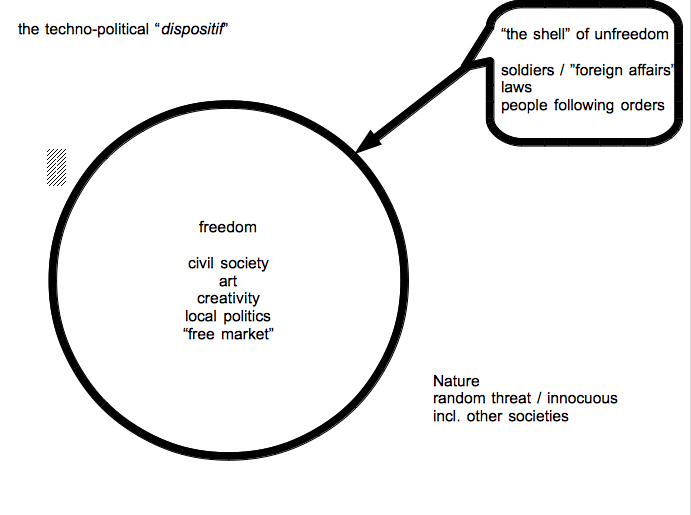

Computers are perfect instruments to be employed in military and police work because they behave absolutely, invariably according to command protocols. There is no freedom in a computer, if there were any freedom in the computer, it would not work. The implementation of computerization into social, civil sphere as well means that technology more applicable for discipline s being used “freely” the result is a certain militarization of the civil sphere, and uncomfortable overweening transgressions of the state through shared computational protocols into everyday life in the civil sphere. Networked computers truly bring into being a Cyber-social realm where discipline is not only cultural but structural, new forms of freedom will thereby be engendered but ever more informed by computational discipline.

The philosophical problem in understanding our societies as a trade-off between discipline and freedom has troubled humanity since the first civilizations. The society where the excesses of State control can be relaxed will mean that ordinary everyday discipline will have to take up the slack. Cultural forms, traditional religious mores etc. have customarily provided this discipline. The International should in principle do away with the need for borders and the military ”defense department” prerequisites for civil peace, but until the “lutte finale” towards the International has has been victorious, every nascent communistic society of any scale will need a military and face the same problematic trade-off.

Historically there have been some promising results in the experiences of the USSR, East Germany, China and Vietnam, we can see the hints of what a society where the understanding of the trade-off between discipline and freedom has been engaged more maturely. We can see there the problem is not technology but social structure and the only way to improve concepts of social structuring and provide sustainable innovations is to study existing societies carefully. How well the prevalent computational vector of knowledge production will be able serve that kind of study remains to be seen. It is evident however, that the reduction of everyday desperation about the capacity for any participant to engage in social production can provde enormous increatses in in the ingenuity and assiduity of the general intellect, with or without computation.

The absolute discipline in the micro-, nano-mechanical functioning (on the level of the chemical composition of CPU functionality) is what provides the emancipatory potential (freedom from toil)

Marx wanted to elimate work because he wanted to eliminate toil – an alienated labour deprived of its social integrity through capitalist exploitation. Work without exploitation is not work in that sense. But what happens is: Capital manages to extract value also from activities which are not perceived as being work, that are offered up voluntarily as a part of our unspoken social compact. “Everyday Communism” in acts such as picking up deliveries for neighbours on vacation, watching somebody’s bag, or helping someone with advice, are not commonly considered work, and are not usually remunerated, but contribute to the life of the worker, and therefore to her ability to work for Capital As such “everyday communism” is also indirectly exploited through the capitalised worker.

Likewise the deeply embedded work or toil of the reproduction of the capacity to work, “reproductive labour” as Silvia Federicci calls it. Reproductive labour is on the first level domestic labour, the feeding, clothing, and the many ways of caring for the worker’s capacity to produce work to be sold to the capitalist. The wage earned by the worker is thus not only for the hours of work performed directly by that person but also of the network of unpaid contributions to the capacity to work.

The reproduction of the labourer’s capacity to work also depends on agriculture and the distribution of food, provision of clean water, nowadays also electricity, transportation to and from work, shelter and many other assumed resources, which the capitalist who employs the worker need not provide. Much of these requirements for the reproduction of the labourer are supplied by the state, under capitalism as a subsidy to business. Especially on the federal level in a capitalist system, workers are taxed, but receive only benefits which subsidise their employer. Under neo-liberalism, necessities provided by the state at moderate cost are being privatised. This means rather than public spending subsidising reproductive labour, workers pay fees from the wages they receive from capital to other capitalists.

Capital’s unbending requirement to derive maximal profits disciplines the worker. Adam Smith praised the productivity gains of the division of labour, which, industrialised and scientifically managed through Taylorism, lead to pervasive automation in production of socially necessary goods and services. Amazon workers in the “fulfillment” center are part of a machine-human symbiotic labour-unit where the human part is subject to a control regime which is constantly adjusted to maximize productivity. The non-mechanical, intangible quality of the human participant is assumed as part of the wage, as 50 years before on the Ford or Lada assembly line, workers were evaluated on the number of pieces completed per hour, the psychological and emotional work they performed internally which made their physical performance possible and sustainable for day after working day was an intangible, expected ancillary labour on top of the that demanded by the employer.

Automation has always been there to discipline the worker in order to maximize profits. Automation of the workplace and contemporary capitalism are indistinguishable. The perfunctory modernization and industrialization programs in the former Soviet Union, in China and elsewhere in the early and mid-20th century were the application of automised techno-industrial (Taylorist) means borrowed from capitalist enterprise, with all their profit-oriented performance metrics, towards nominally socialist ends. It is not surprising that they failed to produce the ideal society for which they were invoked. Not only the regimented and alienating performance-oriented discipline in the factories but even the understanding of an emancipated society based on mass-production materials in general is fundamentally flawed. On a collective farm, the step from ox and hoe to petroleum-burning tractor is not simply progress, it is the disciplining of materials (in this case metals) into a robotic form made of standardised and replaceable parts, which in turns, disciplines the farmers into being appendages of the apparatus. The massive scale agriculture of the 20th century is a product of standardization-automization and the machines are a product of a way of looking at labour which is utilitarian and abstract from the integrity of the living labourer and its society..

A civilization for which the emancipation of every member is the absolute priority will have to approach automation as a very dangerous concentration, in the way certain herbal or mineral extracts are poisonous in an undiluted state but can heal at lower concentrations. The problem is that we need the entirety of the globalized techno-industrial dispositif to produce the high technologies we invest so much hope in today, and this cannot be moderated. It seems the problem is either all or nothing.

This is where technological disobedience comes in. Technological disobedience, a term coined by Cuban-American artist Ernesto Oroza, calls us to use technological products in ways which were not intended by the manufacturer and also for longer than intended. It aims to curtail the demand for new production of automation by deriving better products based on technologies which are slightly behind the “cutting edge”. These technologies, already magnificent feats of human engineering science and the techno-miracle of collaboration (albeit under capitalist discipline) on a global scale have so much under-utilized potential. It is an obscene waste to simply dispose of these highly sophisticated and capable instruments, but they are not built with repurchasing in mind. Technological disobedience, through generating alternative automatised economies of scale where access to cutting edge instruments is difficult, and by reducing demand for cutting edge industrial products, can contribute to a moderation of the particular prevalent innovation vector in automated capitalism and perhaps open up somewhat the field for other modes of technical innovation which do not serve capital so effectively.

The wider availability of re-purposed electronics can also support an ecosystem of software which can perform excellently on older machines. One of the principle objectives of counterantidisintermediationists is to design robust networked communications functionalities which do away with the need for centralized server architecture. Each participant on the network provides both storage spce and computationality and the application runs distributedly on the ad hoc network which cannot be owned but only shared. Such a network could ideally be used to coordinate communal production and distribution as well as to provide capacities for forms of research and exchange of information and ideas which are less under the pressure to produce exchange value from still prevalent capitalism.

The machines, and automation themselves are not the enemy, they simply avail capital of great means to instrumentalise and disenfranchise our living capacity. The vision, imagined by Marx and Engels, anarchists and communists, of general emancipation from desperation and subjugation, requires not more automation but rather a transitional re-purposing of existing automation for the specific computational and productive needs of communist communities, i.e. how to federate communal production, how to efficiently reproduce the infrastructural requirements (water, sewage, health care, elder and child care, etc. ) for a self-emancipating society, and how to do all this in a way that, under constant pressure from prevalent capitalism, maintains its domain of autonomy over the conditions of reproduction.

The machines themselves, computational and otherwise, and the immense miraculous techno-industrial dispositif which reproduces them and their ability to function, operate on fundamentally unfree principles. The globalised logistics chains, the dickensian conditions in tungsten mines, the reliable functioning of the power grid, all requires unquestioning discipline. Who will contribute that discipline under what conditions? What is the trade-off? How can we elaborate the notion of freedom anew in a way that integrates acknowledgment of the ambient social requirement to subjugate ones own freedom for the benefit of all? Technologies re-imagined to serve global emancipation and redistribution of socially necessary discipline are urgently required.